Originally published in SADMag in August 2014. By Claire Atkin and Murray McKenzie. Graphics by Adam Cristobal.

When Andy Yan, urban planner and researcher at Bing Thom Architects, wants to illustrate the need for regional thinking in Vancouver, he first shows his audience an image they all recognize. It is a postcard-perfect aerial photo of the downtown peninsula from across False Creek on a beautiful day. Stanley Park, the Burrard Inlet, and the foot of the Coast Mountains peek through glass residential towers. In the urban planning community—and, increasingly, beyond it as well— that unmistakable vista signifies a global brand of planning and design achievement.

Next, Yan shows an aerial photo that few in the crowd have seen before. The Vancouver skyline is in the foreground, but beyond it a city sprawls as far as the horizon, across the broad Fraser River floodplain. His audience leans in for a closer look. Prior to this, many of them may never have even wondered how this opposing view might appear. And few would be able to confidently point to where Vancouver ends and Burnaby begins, and then New Westminster, Coquitlam, Surrey, and so on.

The fact is, notwithstanding the well-worn images we all hold in our collective self-identity, the second photo has a lot more to say about what Vancouver is and what it could become. Population data suggests that it’s an image with which we should all be more familiar: in 2011, almost 2.4 million people lived in Metro Vancouver, representing a little over half of British Columbia’s total population. But of that 2.4 million, only about 4% of them (99,233) resided on the downtown peninsula. Throw in the adjacent neighbourhoods of Kitsilano, Fairview, Mount Pleasant, and Strathcona, and we still have only 9% of the region (210,606) living in the vicinity of that well-known skyline. Not pictured: the other 2.2 million residents, still almost half of the provincial population, living elsewhere in the mostly suburban, mostly uncelebrated Vancouver region.

Collectively, what do those suburban areas look like? To be sure, they’re much more than a sprawling expanse of “bedroom communities”—so-called because they’re full of houses for sleeping in and not much else. The Vancouver region is looking increasingly like a network of urban centres. They may not challenge the central area for regional dominance, but they are coming into their own as vibrant and economically productive nodes on the suburban map. Impressively, as Surrey’s population has grown, its share of residents commuting outside of the municipality for work has dropped; it’s gaining jobs at least as fast as it’s gaining residents.

This is good news for transportation planners worried about the exploding commute times observed in many classically sprawling North American cities. In fact, the most notable landmarks in our lesser-known suburban skyline are the clusters of high-rises that mark the location of SkyTrain stops. Transit-oriented development is one of the most important things we can pursue in an era of environmentally aware regional planning.

What are the Suburbs?

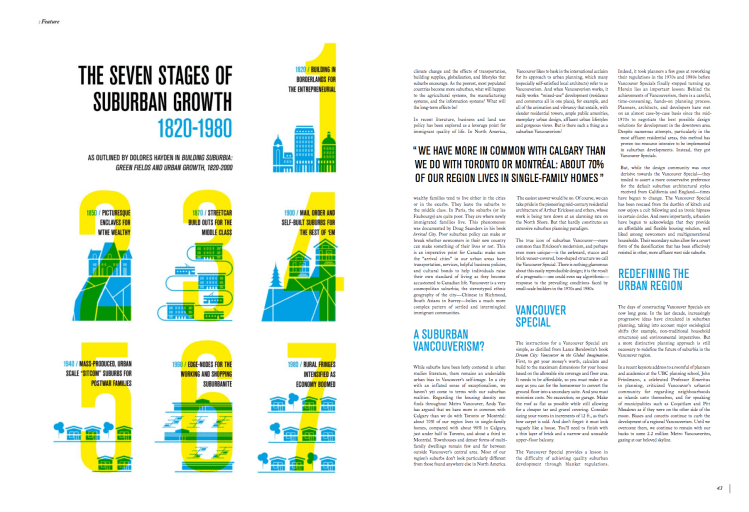

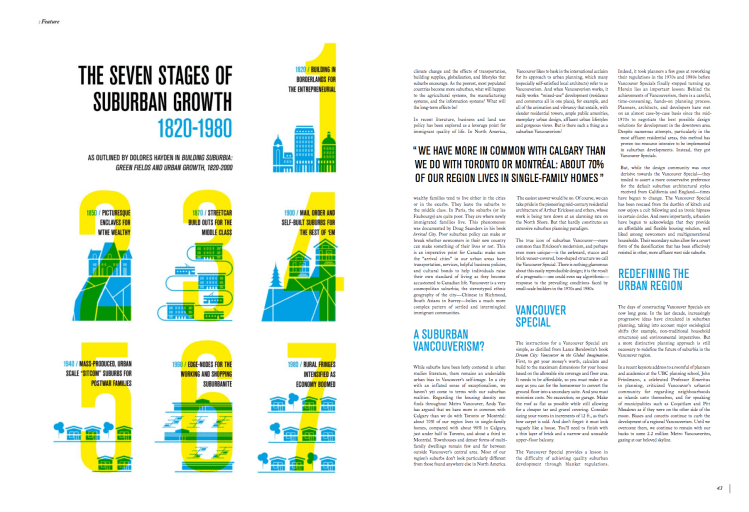

The North American suburbs are commonly understood as a reflection of postwar futurism, widespread car ownership, changing racial tensions, and an enduring government-encouraged obsession with home ownership. Early during the rise of manufacturing in North America, suburban entrepreneurs started buying plots to subdivide and develop as experiments. Political alliances formed between groups of land developers. As this process became increasingly systematic, development encroached further and further out into urban peripheries.

Spurred by industrial capitalism, real estate development quickly became a sophisticated field with partnerships with utilities companies, transit owners, and local government. As federally mandated tax, banking, and insurance systems began to favour powerful real estate lobbies through the 1920s, publicly subsidized highway systems, utilities, and even private residential and commercial real estate provided growing incentives for massive suburban growth. The results are what we are left with today.

Suburbanism as Culture

Home ownership. Car ownership. Furniture ownership. These are the things that suburbs are made of in North America. The suburbs have defined our cultures beyond what we might imagine.

In Vancouver, conflict caused by suburban expansion can be seen daily in the news. The highway system, the SkyTrain system, and the bike routes (oh, the bike routes!) are political because of suburban drivers who must be accommodated on their daily commute.

There is a growing cultural concern around how suburbs will develop over time. Humans became over 50% urbanized (mostly suburbanized) in the last two years, for the first time in history. What we do with these suburbs will affect more than four billion people over the course of their lifetimes. It will also affect the environment, if we account for climate change and the effects of transportation, building supplies, globalization, and lifestyles that suburbs encourage. As the poorest, most populated countries become more suburban, what will happen to the agricultural systems, the manufacturing systems, and the information systems? What will the long-term effects be?

In recent literature, business and land use policy has been explored as a leverage point for immigrant quality of life. In North America,Vancouver likes to bask in the international acclaim for its approach to urban planning, which many (especially self-satisfied local architects) refer to as Vancouverism. And when Vancouverism works, it really works: “mixed-use” development (residence and commerce all in one place), for example, and all of the animation and vibrancy that entails, with slender residential towers, ample public amenities, exemplary urban design, affluent urban lifestyles and gorgeous views. But is there such a thing as a suburban Vancouverism?

Indeed, it took planners a few goes at reworking their regulations in the 1970s and 1980s before Vancouver Specials finally stopped turning up. Herein lies an important lesson: Behind the achievements of Vancouverism, there is a careful, time-consuming, hands-on planning process. Planners, architects, and developers have met on an almost case-by-case basis since the mid- 1970s to negotiate the best possible design solutions for development in the downtown area. Despite numerous attempts, particularly in the most affluent residential areas, this method has proven too resource intensive to be implemented in suburban developments. Instead, they got Vancouver Specials.

But, while the design community was once derisive towards the Vancouver Special—they tended to assert a more conservative preference for the default suburban architectural styles received from California and England—times have begun to change. The Vancouver Special has been rescued from the dustbin of kitsch and now enjoys a cult following and an ironic hipness in certain circles. And more importantly, urbanists have begun to acknowledge that they provide an affordable and flexible housing solution, well liked among newcomers and multigenerational households. Their secondary suites allow for a covert form of the densification that has been effectively resisted in other, more affluent west side suburbs.

Redefining the Urban Region

The days of constructing Vancouver Specials are now long gone. In the last decade, increasingly progressive ideas have circulated in suburban planning, taking into account major sociological shifts (for example, non-traditional household structures) and environmental imperatives. But a more distinctive planning approach is still necessary to redefine the future of suburbia in the Vancouver region.

In a recent keynote address to a roomful of planners and academics at the UBC planning school, John Friedmann, a celebrated Professor Emeritus in planning, criticized Vancouver’s urbanist community for regarding neighbourhoods as islands unto themselves, and for speaking of municipalities such as Coquitlam and Pitt Meadows as if they were on the other side of the moon. Biases and conceits continue to curb the development of a regional Vancouverism. Until we overcome them, we continue to remain with our backs to some 2.2 million Metro Vancouverites, gazing at our beloved skyline.

“ We have more in common with Calgary than we do with Toronto or Montréal: about 70% of our region lives in single-family homes ”

Wealthy families tend to live either in the cities or in the exurbs. They leave the suburbs to the middle class. In Paris, the suburbs (or les Faubourgs) are quite poor. They are where newly immigrated families live. This phenomenon was documented by Doug Saunders in his book Arrival City. Poor suburban policy can make or break whether newcomers in their new country can make something of their lives or not. This is an imperative point for Canada: make sure the “arrival cities” in our urban areas have transportation, services, helpful business policies, and cultural bonds to help individuals raise their own standard of living as they become accustomed to Canadian life. Vancouver is a very cosmopolitan suburbia; the stereotyped ethnic geography of the city—Chinese in Richmond, South Asians in Surrey—belies a much more complex pattern of settled and intermingled immigrant communities.

A suburban Vancouverism?

While suburbs have been hotly contested in urban studies literature, there remains an undeniable urban bias in Vancouver’s self-image. In a city with an inflated sense of exceptionalism, we haven’t yet come to terms with our suburban realities. Regarding the housing density one finds throughout Metro Vancouver, Andy Yan has argued that we have more in common with Calgary than we do with Toronto or Montréal: about 70% of our region lives in single-family homes, compared with about 90% in Calgary, just under half in Toronto, and about a third in Montréal. Townhouses and denser forms of multi- family dwellings remain few and far between outside Vancouver’s central area. Most of our region’s suburbs don’t look particularly different from those found anywhere else in North America.

The easiest answer would be no. Of course, we can take pride in the pioneering mid-century residential architecture of Arthur Erickson and others, whose work is being torn down at an alarming rate on the North Shore. But that hardly constitutes an extensive suburban planning paradigm.

The true icon of suburban Vancouver—more common than Erickson’s modernism, and perhaps even more unique—is the awkward, stucco and brick veneer-covered, box-shaped structure we call the Vancouver Special. There is nothing glamorous about this easily reproducible design; it is the result of a pragmatic—one could even say algorithmic— response to the prevailing conditions faced by small-scale builders in the 1970s and 1980s.

Vancouver Special

The instructions for a Vancouver Special are simple, as distilled from Lance Berelowitz’s book Dream City: Vancouver in the Global Imagination. First, to get your money’s worth, calculate and build to the maximum dimensions for your house based on the allowable site coverage and floor area. It needs to be affordable, so you must make it as easy as you can for the homeowner to convert the ground floor into a secondary suite. And you must minimize costs. No excavation; no garage. Make the roof as flat as possible while still allowing for a cheaper tar and gravel covering. Consider sizing your rooms in increments of 12 ft., as that’s how carpet is sold. And don’t forget: it must look vaguely like a house. You’ll need to finish with a thin layer of brick and a narrow and unusable upper-floor balcony.

The Vancouver Special provides a lesson in the difficulty of achieving quality suburban development through blanket regulations. Indeed, it took planners a few goes at reworking their regulations in the 1970s and 1980s before Vancouver Specials finally stopped turning up. Herein lies an important lesson: Behind the achievements of Vancouverism, there is a careful, time-consuming, hands-on planning process. Planners, architects, and developers have met on an almost case-by-case basis since the mid- 1970s to negotiate the best possible design solutions for development in the downtown area. Despite numerous attempts, particularly in the most affluent residential areas, this method has proven too resource intensive to be implemented in suburban developments. Instead, they got Vancouver Specials.

But, while the design community was once derisive towards the Vancouver Special—they tended to assert a more conservative preference for the default suburban architectural styles received from California and England—times have begun to change. The Vancouver Special has been rescued from the dustbin of kitsch and now enjoys a cult following and an ironic hipness in certain circles. And more importantly, urbanists have begun to acknowledge that they provide an affordable and flexible housing solution, well liked among newcomers and multigenerational households. Their secondary suites allow for a covert form of the densification that has been effectively resisted in other, more affluent west side suburbs.

Redefining the Urban Region

The days of constructing Vancouver Specials are now long gone. In the last decade, increasingly progressive ideas have circulated in suburban planning, taking into account major sociological shifts (for example, non-traditional household structures) and environmental imperatives. But a more distinctive planning approach is still necessary to redefine the future of suburbia in the Vancouver region.

In a recent keynote address to a roomful of planners and academics at the UBC planning school, John Friedmann, a celebrated Professor Emeritus in planning, criticized Vancouver’s urbanist community for regarding neighbourhoods as islands unto themselves, and for speaking of municipalities such as Coquitlam and Pitt Meadows as if they were on the other side of the moon. Biases and conceits continue to curb the development of a regional Vancouverism. Until we overcome them, we continue to remain with our backs to some 2.2 million Metro Vancouverites, gazing at our beloved skyline.